What It Was Really Like to Come Out…as Asexual, with ADHD, as Gay, and Then Finally as My Fully Authentic Self

Editor's Note: This post originally published in October 2023. It was updated in October 2024.

###

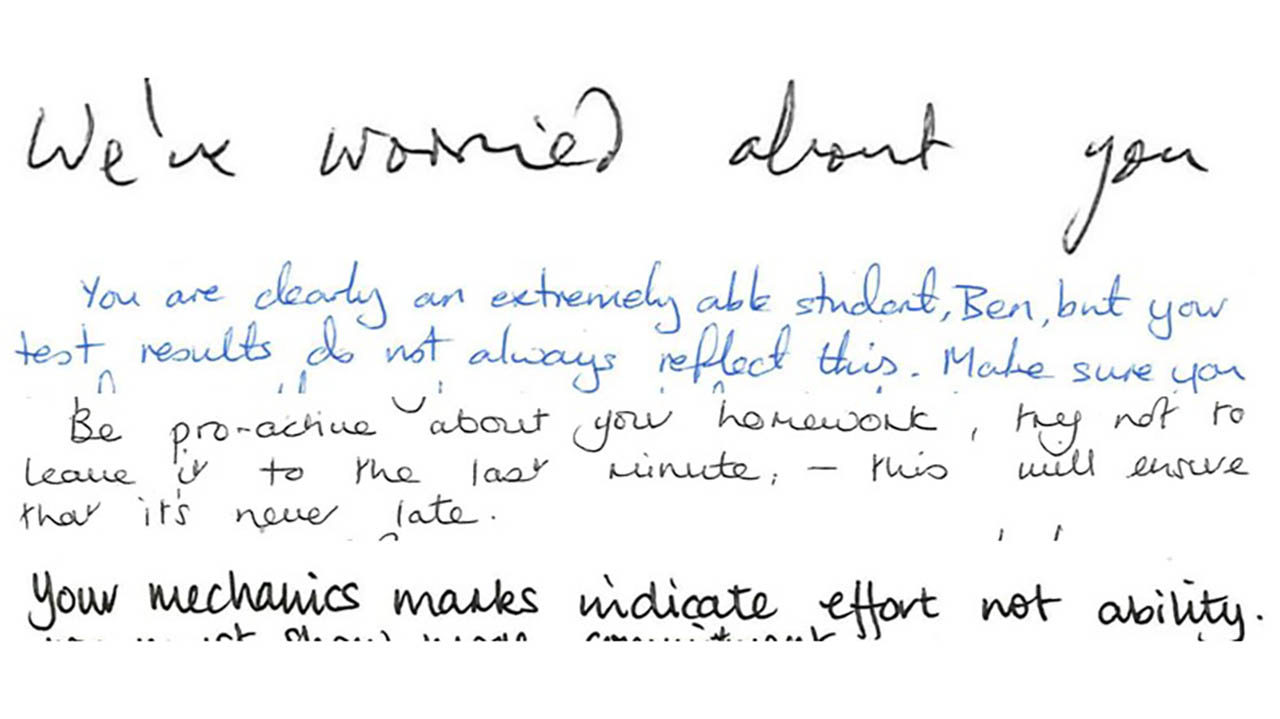

From a young age, I always sensed I was unlike my peers. I just never knew why and, quite honestly, thrived on being different for many years. Throughout my primary and secondary school years (ages 4-16), being different had its advantages. My natural knack for absorbing knowledge, coupled with an insatiable curiosity about the inner workings of things, consistently positioned me at the top of the class in almost every subject—except handwriting. While I occasionally played the class clown, I never disrupted the learning environment, earning favour with my teachers.

But at some point, I realized that being different from others and acting different from who you are inherently at your core are not the same thing. The former should be celebrated. The latter should be explored with a certain curiosity and intent to correct. There are consequences to living inauthentically, including tremendous suffering. I know this all too well.

That’s why I first wrote this blog post – my coming out story – over a year ago.

I don’t want anyone to have to go through the same pain that I did. If my story helps just one person understand themselves, or their child, or loved one, then I know it is worth it. I have been very open with my ADHD diagnosis as I’m sure my team would profess; I don’t seem to shut up about it! But already three people within our office have realised their life stories have a lot of similarities to mine, two people within my theatre society have since been diagnosed with neurodiversity, and one friend from university is looking to get a diagnosis; not for his sake but for his children as ADHD is highly genetic.

Now, you might be wondering why it took me a year to actually publish this post that I wrote in October 2022.

Well, if I’m being honest, before I realised I had ADHD I would have told you that coming out wasn’t important to me. I didn’t see the need to share my personal experiences with my work colleagues, much less the world. I had identified as asexual for a long time, which meant that I didn’t feel that I was hiding much from anyone as, for example, I wasn’t going to gay bars or feeling uncomfortable in my own body. So, after I received my ADHD diagnosis, started treatment, and started having the clarity of thought and emotion to recognize my true sexuality (that I was in fact gay, not asexual), it was hard to come out and say I was someone different than others knew me to be – even if this person is in fact the real me. The underlying and significant homophobia present within society during my formative years made me repress my sexuality so much I didn’t realise I might be gay until I was 23! And then I spent years saying I wasn’t gay. That’s hard to just put out there casually to the world.

On top of that, there is also a lot of stigma around ADHD and its symptoms as well as many other neuro and physical diversities. So, my coming out requires me to help others who I really am, and that requires me to help them understand neurodiversity, asexuality (and how that’s different from being gay), etc. – all of which I’m still trying to understand myself.

There’s always a breaking point, though – a moment in time when the benefits outweigh the risks.

In my case, the semi-conscious camouflaging of my neurodiversity and the repressing of my sexuality was taking so much effort and energy from me, and the coping mechanisms that I had created to fit in over the years were so exhausting, that I decided it was time to show myself to the world.

Understanding and admitting who I am to my colleagues – and to you, who may be a perfect stranger – does make me feel vulnerable. But it also makes me feel free. My colleagues and community know how to support me with things I’m not good at, and they know they can ask for help from me with things in which I have strength. But most importantly I hope they now feel I am being my authentic self and trust them with who I am.

Plus, as the EMEA lead for Zebras of All Abilities (ZoAA), an employee resource group, I have been trying hard to dispel the stigma and help educate and support our community. There are also a lot of benefits to ADHD: hyper-focus, enhanced creativity, resilience, adventurousness, even simply diversity of thought. By letting people be true to themselves and understand their capabilities they can be the best person that they can be.

So, without further ado, here’s what it has been like to be me the last several years. Can you or someone you know relate?

What I Learned in School: How to Make Myself Likeable

I thrived socially at school, adept at understanding people's personalities and adjusting my own: emphasising certain traits and repressing others to make myself more likable. I loved being liked; it gave me such a rush!

Unfortunately, due to the prejudiced atmosphere in my deprived state school in the early 2000’s, strengthened by the appalling homophobic Section-28 law introduced in the UK 12 years prior, certain aspects of my personality were repressed strongly and constantly. It was at this point I felt I lost my true personality.

As I approached the end of my school years, studying for my General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) exams became an insurmountable task, despite my mother's increasingly exasperated nagging. I wasn't overly concerned, though, as my talent for absorbing and regurgitating knowledge had always seen me through. Although my grades were good, perhaps not quite living up to my teachers' expectations, most of them were A's. Yet, my handwriting remained atrocious.

Next came college and I started to fall behind. My grades started slipping in the six subjects I had taken, I couldn’t do my coursework in time, my exam grades were not reflective of what I was capable, so in shame I attended fewer and fewer lessons.

At the same time my relationships with my friends were deteriorating. They all started getting girlfriends and just wanted to do boring things like go to noisy pubs and bars, or just sit and watch TV, none of which I had any interest in. I couldn’t figure out what had gone wrong. I had been so happy and successful at school, yet one year later I felt like a failure. I couldn’t talk to any of my friends; I had never been able to ask for help from anyone. The fear of being seen as weak was unbearable in the macho, competitive social climate in which I was living. I fell ill with depression which lasted 16 years.

While I didn’t get accepted to Oxford or Cambridge University as was expected of me, I did go to another less well-known university to study computing. (Finally, no more handwriting, I thought)! Computing was a natural fit for me. I thrived again at quickly absorbing concepts and knowledge that interested me but again could only revise by cramming the morning before an exam; all my coursework was started the night before the deadline, generally at 2am. I was incapable of doing it earlier. Exams got harder as well, not because I didn’t know the content, but because my hand just could not move fast enough to write down the answers in the allocated time.

I eventually handed in my Master’s dissertation 33 days late. I had written it entirely in the final five days of that, with no sleep and 60 cans of energy drink.

I felt mentally battered and bruised coming out of university. There were some incredibly stressful times that I felt were entirely my fault. “Why didn’t you just start the coursework sooner you fool?!” I would think following a coursework all-nighter but when the next piece of coursework would come around, I would be found yet again working through the night before.

The five years I was at uni, the milieu changed significantly. In my first year, the familiar homophobic atmosphere from school was still the norm; but positive progress was palpable throughout my time at uni. By the final year, homophobia and prejudice were openly challenged, and I had formed a close friendship with someone who was openly gay for the first time. His friendship was transformative for me. I initially could not comprehend why someone would willingly make themselves so publicly vulnerable by being out; but through witnessing his bravery, self-confidence, strong sense of social justice, authentic vulnerability, and selflessness, the stoic, maladaptive social constructs in my mind started crumbling.

Finding Peace with “Chaotic Coding”

It was time to join the workforce. Thankfully I applied to Motorola, and James Morley-Smith hired me into his team within the enterprise mobile computing business unit. I finally felt I was where I could excel, as the work I was doing was fascinating and exactly what I wanted to do: coding! I did seem to jump around the code quite a lot – five minutes here, five minutes there (a term I named “chaotic coding”) – but the work got done. I was able to apply my creative side as well, submitting eight patents in the first two years, five of which went through to issuance.

Later, James re-hired me into his new team within Innovation & Design at Zebra where I am today, leading the front-end development team. Being within Innovation & Design, I get to flex my creative side more than most engineers have the opportunity to, especially working alongside the User Experience Design team.

But being a manager was much more difficult than being an engineer. There were things I struggled at, especially organisation, time estimation for projects, starting what seemed to be insurmountably big tasks, and putting finishing touches to things once the majority had been done. But I slowly found ways to adapt, putting processes and tools in place to fill my deficiencies. While I would keep on top of project work, my to-do list grew longer and longer with tasks that would have benefited the team greatly but had no deadline.

Then came COVID.

I Had an Epiphany

When the government told us we had to work at home, I panicked at first. I’d previously hated working from home, I just couldn’t do it. But similar to management, I learnt to cope...with chocolate.

Since I’m being honest here, my coping mechanism turned into an addiction, and with mandated limited access to the outside, my weight increased. I was never at a weight I was happy with since falling ill with depression, but a year after the first COVID lockdown started I was at my heaviest. So, I made sure to make the most of our government-mandated one exercise period per day and went for walks at lunchtime.

It was one afternoon when driving to my favourite walking spot I had BBC Radio 4 on in the background. A programme called “The Listening Project” was on, where two people would have a conversation with one another. They may have known each other for a lifetime, or never met before; the only thing needed was a connection. The two ladies talking in this episode were conversing about how they’d both been diagnosed in their 60’s with ADHD and how it had affected them through their lives. My jaw dropped, I had to stop the car. It was like they were describing my life in its entirety. I immediately drove home and tried to absorb all the information I could find about ADHD.

My world at that point got so much bigger yet so much smaller at the same time. I started furiously researching ADHD and, surprisingly, finding so much out about myself. So many things that I thought made me unique were easily explained by this condition, such as my chocolate addiction, as well as my chaotic coding and challenges learning to manage people.

For example, I quickly came to understand that ADHD is a neurodiverse condition that has a long list of “symptoms” which can often be shared with other neurodiverse conditions. People with ADHD may exhibit very diverse sub-sets of these, which is why it is such a misunderstood condition by the general public.

The common ones that I experience (which I now know are in fact typical with ADHD) are:

· Bad working memory/short term memory – If neurotypical people can hold six things in their working memory, people with ADHD may only be able to hold four. A person with ADHD often therefore uses an “external memory” like taking notes during meetings or asking others to remember things for them. “Can you remind me I need to take the cat to the vet tomorrow”? Answering multi-part questions can make them feel embarrassed, as they may only remember the first part of the question.

· Hypersensitivity – Finding certain tastes, sounds, and touch unbearable. Feeling emotions more acutely than others, together with the social difficulties this can cause.

· Poor fine motor control – i.e. handwriting!

· No distraction filter – Requires constant effort to be able to ignore distractions. Makes working memory worse, as the distraction may push out something else before being ignored. Background music is one of the most common distractions.

· Auditory perception disorder – Not being able to make out voices over noise, sensory overload in noisy/busy places, such as pubs, clubs, etc.

· Time blindless – Poor perception of time, causing some to be persistently late or being unable being able to estimate time accurately.

· Hyperfocus – often at the expense of everything else (eating, drinking, sleeping, appointments). When in a hyper focused state, a person with ADHD may do super-human levels of work or creativity non-stop for long periods of time.

· Forgetting words – People with ADHD often forget particular words that they are trying to use. This does mean people with ADHD generally have wider vocabularies to be able to fill the gap with similar words.

· Motivation issues – ADHD is associated with lower levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which affects the ability to perform tasks solely out of a sense of obligation. Individuals with ADHD typically require additional sources of motivation, such as novelty, personal interest, or, more commonly, anxiety. Anxiety is the fear of something bad happening, such as someone being angry, or being about to fail a course. Therefore, a person with ADHD leaves things to the very last minute, as the later it gets the more the anxiety builds. So, if a task has no strict deadline, it will never get done and that to-do list will never get shorter.

· Intolerance of prolonged tasks – The lack of dopamine also affects how long a person with ADHD can do a task. It can get physically uncomfortable sticking on the same task for a long period of time, this is why I code chaotically, flitting from one part of the code to another. And once the anxiety passes, once enough of the task has been completed, the motivation then disappears. This is why tasks are difficult to complete once the majority has been done.

There are several ADHD traits that I'm less acquainted with because I don't display them, with hyperactivity being a significant one. Non-hyperactive ADHD is more prone to going undiagnosed into adulthood. Children, especially boys, who primarily exhibit hyperactivity tend to receive early diagnoses due to the disruptive impact of their behaviour in school. However, for others, the enduring stereotype of ADHD revolves around the disruptive child, which can lead to underdiagnosis.

It's important to note that girls often face greater peer pressure to conform and suppress their hyperactivity, which unfortunately results in fewer diagnoses among females.

There are also comorbidities (conditions) which often show with ADHD, which include Autistic Spectrum Disorder, depression, anxiety disorders, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria, Oppositional Defiance Disorder, tics, language disorders, and many more.

Confirming My Suspicions

Armed with all this knowledge and knowing how significantly ADHD had affected my life, I was determined to do something about it. My general practitioner (doctor) quickly confirmed that she’d be happy to refer me for diagnosis, but with the COVID situation, the waiting list for diagnosis on the NHS had reached two years.

I decided to pursue a private diagnosis instead. At the time*, Zebra’s private medical insurance specifically excluded ADHD (and ASD), so I had to self-fund. Four months & £3000 later I finally got my diagnosis of moderate/severe ADHD with possible “very highly camouflaged” ASD traits.

(*Zebra has since updated its UK Private Healthcare policy, with support for neurodiversity cover, following advocacy from the ZOAA employee resource group and support from the EMEA HR team.)

On the Road to Recovery – or Rediscovery

Following my diagnosis, I was presented with the options on how to deal with my condition. I knew early on that I was going to want medication. I was prescribed the stimulant Lisdexamfetamine (Elvanse/Vyvanse). Being a potent controlled substance (Class-B in the UK, related to Crystal-Meth), the increase in dosage had to be done gradually. But even after the taking the first pill on the first day I knew this medication would be life changing. Within an hour of taking the lowest dose I felt my head become clearer, my thoughts become more ordered. By the end of the day, I had done eight things from my to-do list – the to-do list that hadn’t had anything done from it for years.

Now at work I can stick with tasks, no more chaotic coding; but more importantly I am able to do those non-deadline-based tasks. These are the real blue-chips, the strategic things which can really make a positive change to the company. My memory is better, I hold better conversations, I talk quieter.

Within the first 18 months after realising I had ADHD, I lost 30kg (66lbs). I have now maintained a healthy weight for over a year which I hadn’t been in for over a decade. The reason why I could lose the weight was because I had the motivation to be able to say “no” to bad food, the organisation to buy the right food at the supermarket, and the ability to form a routine of healthy eating and exercise. Most importantly, when I’m on the medication, I have no chocolate addiction. Prior to my diagnosis and treatment, I was eating on average 250g (½ lb) of chocolate a day, as without it I would get extremely restless and irritable and wouldn’t be able to function, just like other addictions. I learnt that the reason I had this addiction was because I was unknowingly self-medicating my ADHD. Chocolate creates dopamine.

My New Life (Update Since I Started Writing This Post)

It has now been a little over a year since I settled on a stable dose of medication and a lot has changed. It feels like my life has finally started. While I dealt with my long-term depression a couple of years before my ADHD diagnosis, I have now realised the cause of it was the social difficulties caused by my ADHD. I am now confident that the depression is never coming back.

Within the last year I have achieved a lot that I had previously procrastinated or avoided. I have a personal trainer and regularly go to the gym. I have had a singing teacher for the last year and have joined a local amateur musical theatre society with whom I performed as Lord Farquaad in Shrek and as Benny in RENT.

I have even been on my first ever self-organised holiday. I have completed so many DIY projects in my house, it now looks very different. I know I would not have been able to do any of this without the diagnosis as I would have continued procrastinating forever.

But things aren’t perfect. Over the last few months, I have realised my medication is causing side-effects which are too significant and that I need to find a more suitable medication. I have been sleep-deprived throughout the last year and, while the medication masks the feeling of tiredness, the other effects of sleep deprivation have been making me less productive, less attentive, less social, more exhausted.

Thankfully, through my work with ZoAA and the support of Shelley Eades and her team, *the UK private medical insurance (AXA) now covers Neurodiversity, including ADHD. I have recently started using this pathway to discover more about myself by seeking assessment for my Autistic Spectrum traits.

I have been reflecting on the past and understanding more and more about how my mind works. The most significant discovery which was mentioned in my diagnosis report is that I have social anxiety which I have unconsciously masked with avoidance-based coping mechanisms. I have been attempting to understand, unpick, and reverse these coping mechanisms one-by-one to be able to find my truly authentic-self. The biggest challenge ahead of me is to remove all the coping mechanisms that are masking my sexuality.

But I’m confident I will succeed in doing that as well now that I know who I am, why I am who I am, and that others still love and support me – the real me. My neurodiversity and asexuality haven’t changed anything, other than my understanding and appreciation of who I am, why I am who I am, and the freedom to finally live as my authentic self and still be liked!

(My handwriting is still terrible.)

So, if you feel somewhere deep inside that you are having to “learn to be likeable” or you just don’t know why you are the way you are, I encourage you to be curious. Read or listen to other people’s stories and, if something they say seems to click with you – if you have an epiphany like I did – follow your instincts and investigate. Maybe you don’t have everything in common, but that may just be the moment in time when you can finally get the answers you need to feel comfortable coming out as your authentic self.