Transform retail operations with Zebra’s retail technology solutions, featuring hardware and software for improving inventory management and empowering teams.

Streamline operations with Zebra’s healthcare technology solutions, featuring hardware and software to improve staff collaboration and optimize workflows.

Enhance processes with Zebra’s manufacturing technology solutions, featuring hardware and software for automation, data analysis, and factory connectivity.

Zebra’s transportation and logistics technology solutions feature hardware and software for enhancing route planning, visibility, and automating processes.

Learn how Zebra's public sector technology solutions empower state and local governments to improve efficiency with asset tracking and data capture devices.

Zebra's hospitality technology solutions equip your hotel and restaurant staff to deliver superior customer and guest service through inventory tracking and more.

Zebra's market-leading solutions and products improve customer satisfaction with a lower cost per interaction by keeping service representatives connected with colleagues, customers, management and the tools they use to satisfy customers across the supply chain.

Empower your field workers with purpose-driven mobile technology solutions to help them capture and share critical data in any environment.

Zebra's range of Banking technology solutions enables banks to minimize costs and to increase revenue throughout their branch network. Learn more.

Zebra's range of mobile computers equip your workforce with the devices they need from handhelds and tablets to wearables and vehicle-mounted computers.

Zebra's desktop, mobile, industrial, and portable printers for barcode labels, receipts, RFID tags and cards give you smarter ways to track and manage assets.

Zebra's 1D and 2D corded and cordless barcode scanners anticipate any scanning challenge in a variety of environments, whether retail, healthcare, T&L or manufacturing.

Zebra's extensive range of RAIN RFID readers, antennas, and printers give you consistent and accurate tracking.

Choose Zebra's reliable barcode, RFID and card supplies carefully selected to ensure high performance, print quality, durability and readability.

Zebra's rugged tablets and 2-in-1 laptops are thin and lightweight, yet rugged to work wherever you do on familiar and easy-to-use Windows or Android OS.

With Zebra's family of fixed industrial scanners and machine vision technologies, you can tailor your solutions to your environment and applications.

Zebra’s line of kiosks can meet any self-service or digital signage need, from checking prices and stock on an in-aisle store kiosk to fully-featured kiosks that can be deployed on the wall, counter, desktop or floor in a retail store, hotel, airport check-in gate, physician’s office, local government office and more.

Adapt to market shifts, enhance worker productivity and secure long-term growth with AMRs. Deploy, redeploy and optimize autonomous mobile robots with ease.

Discover Zebra’s range of accessories from chargers, communication cables to cases to help you customize your mobile device for optimal efficiency.

Zebra's environmental sensors monitor temperature-sensitive products, offering data insights on environmental conditions across industry applications.

Zebra's location technologies provide real-time tracking for your organization to better manage and optimize your critical assets and create more efficient workflows.

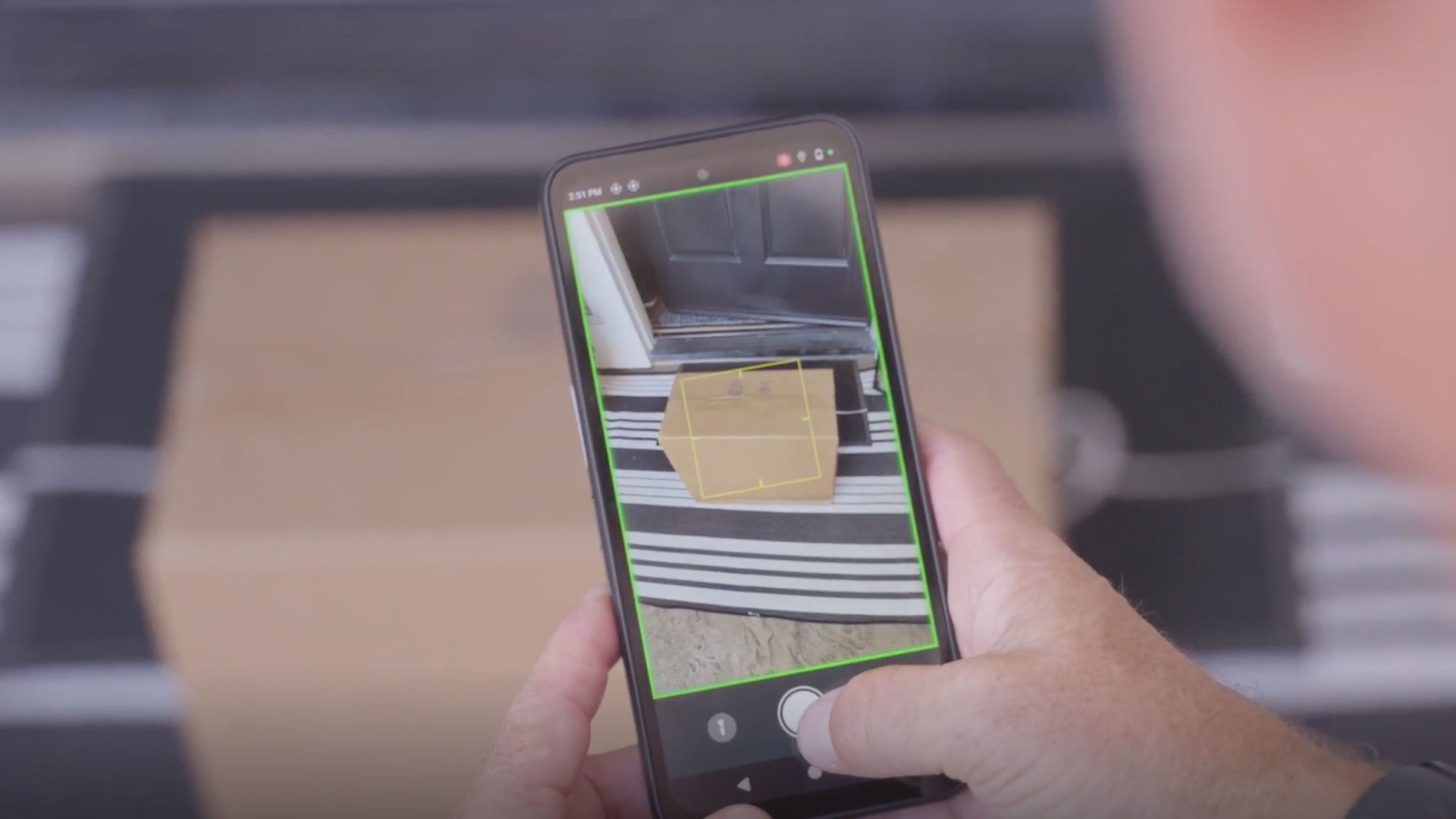

Enhance frontline operations with Zebra’s AI software solutions, which optimize workflows, streamline processes, and simplify tasks for improved business outcomes.

Empower your frontline with Zebra Companion AI, offering instant, tailored insights and support to streamline operations and enhance productivity.

Boost productivity with Zebra Frontline AI Enablers: AI vision models, sample apps, and APIs streamline workflows for efficient business processes.

Zebra Frontline AI Blueprints deliver adaptable, real-world AI frameworks that automate manual tasks and drive efficiency in high-pressure frontline operations.

Zebra Workcloud, enterprise software solutions boost efficiency, cut costs, improve inventory management, simplify communication and optimize resources.

Keep labor costs low, your talent happy and your organization compliant. Create an agile operation that can navigate unexpected schedule changes and customer demand to drive sales, satisfy customers and improve your bottom line.

Drive successful enterprise collaboration with prioritized task notifications and improved communication capabilities for easier team collaboration.

Get full visibility of your inventory and automatically pinpoint leaks across all channels.

Reduce uncertainty when you anticipate market volatility. Predict, plan and stay agile to align inventory with shifting demand.

Drive down costs while driving up employee, security, and network performance with software designed to enhance Zebra's wireless infrastructure and mobile solutions.

Explore Zebra’s printer software to integrate, manage and monitor printers easily, maximizing IT resources and minimizing down time.

Make the most of every stage of your scanning journey from deployment to optimization. Zebra's barcode scanner software lets you keep devices current and adapt them to your business needs for a stronger ROI across the full lifecycle.

RFID development, demonstration and production software and utilities help you build and manage your RFID deployments more efficiently.

RFID development, demonstration and production software and utilities help you build and manage your RFID deployments more efficiently.

Zebra DNA is the industry’s broadest suite of enterprise software that delivers an ideal experience for all during the entire lifetime of every Zebra device.

Advance your digital transformation and execute your strategic plans with the help of the right location and tracking technology.

Boost warehouse and manufacturing operations with Symmetry, an AMR software for fleet management of Autonomous Mobile Robots and streamlined automation workflows.

The Zebra Aurora suite of machine vision software enables users to solve their track-and-trace, vision inspection and industrial automation needs.

Zebra Aurora Focus brings a new level of simplicity to controlling enterprise-wide manufacturing and logistics automation solutions. With this powerful interface, it’s easy to set up, deploy and run Zebra’s Fixed Industrial Scanners and Machine Vision Smart Cameras, eliminating the need for different tools and reducing training and deployment time.

Aurora Imaging Library™, formerly Matrox Imaging Library, machine-vision software development kit (SDK) has a deep collection of tools for image capture, processing, analysis, annotation, display, and archiving. Code-level customization starts here.

Aurora Design Assistant™, formerly Matrox Design Assistant, integrated development environment (IDE) is a flowchart-based platform for building machine vision applications, with templates to speed up development and bring solutions online quicker.

Designed for experienced programmers proficient in vision applications, Aurora Vision Library provides the same sophisticated functionality as our Aurora Vision Studio software but presented in programming language.

Aurora Vision Studio, an image processing software for machine & computer vision engineers, allows quick creation, integration & monitoring of powerful OEM vision applications.

Adding innovative tech is critical to your success, but it can be complex and disruptive. Professional Services help you accelerate adoption, and maximize productivity without affecting your workflows, business processes and finances.

Zebra's Managed Service delivers worry-free device management to ensure ultimate uptime for your Zebra Mobile Computers and Printers via dedicated experts.

Find ways you can contact Zebra Technologies’ Support, including Email and Chat, ask a technical question or initiate a Repair Request.

Zebra's Circular Economy Program helps you manage today’s challenges and plan for tomorrow with smart solutions that are good for your budget and the environment.

The Zebra Knowledge Center provides learning expertise that can be tailored to meet the specific needs of your environment.

Zebra has a wide variety of courses to train you and your staff, ranging from scheduled sessions to remote offerings as well as custom tailored to your specific needs.

Build your reputation with Zebra's certification offerings. Zebra offers a variety of options that can help you progress your career path forward.

Build your reputation with Zebra's certification offerings. Zebra offers a variety of options that can help you progress your career path forward.

"I Feel Bad."

We all get advice every day. Some of it’s good. Most of it’s bad. But rarely do we get one piece of advice, at just the right time, by just the right person, that alters the way we think about the world and our place in it. For me, that advice came from an 80-year-old man, outside of a mud-brick hut, in a tiny town in Ecuador.

Between 2006-2008, I was a United States Peace Corps Volunteer in rural Ecuador, working alongside community members on locally prioritized projects, making about $1.50 a day to “sustain” me. (Though I was paid, the Peace Corps is about as close to “volunteering” as it gets when you’re working in support of the U.S. government.)

The man I mentioned was part of the host family I stayed with in the Northern Andes mountains for the first few months of my tour to help me acclimate to living in Ecuador. This adjustment period is standard practice, as Peace Corps leaders want to ensure the change in culture isn’t too shocking. They want volunteers like me to integrate into the community, to feel comfortable with our surroundings, so we can make the greatest impact while there. The thing is, change takes time, and while 27 months seems like a long time to a 23-year-old, it isn’t a long time to the communities in which we work. So, the real goal in this volunteer role, I quickly realized, is to build relationships with people in these countries and exchange cultures and knowledge.

It’s been more than 15 years since I left Ecuador, but there is still one relationship and cultural exchange that sticks with me. Despite having lived in Ecuador for more than two years, the memory (and the story) that sticks with me came from my first night in the country.

Shortly after arriving in my town, my host family (really, my host mother) taught me how to kill a goat and a dozen-or-so guinea pigs, which they had been raising specifically for this night for more than a year. It was a celebratory welcome meal, at least from their perspective. For me, it was uncomfortable.

While we huddled in the smoke-filled hut, cooking the meat they had just slaughtered, my new family asked me about the United States, about whether I went to college, about where else I had travelled. I told them – or at least I tried to tell them – that I grew up 20-minutes from the beach in California, that I graduated from UC Berkeley (I left out that it had recently been awarded one of the best universities in the world), and that I had traveled throughout Europe, parts of Africa, and a few other countries in South America.

I had never felt more privileged – and bad for it – than I had that night. My host family literally could not leave their town because they need to milk their cows twice a day or they’d die. And here I was, inadvertently touting how great my life had been to the poorest people I had ever met. It was painful, in more ways than one.

While I spoke some Spanish, I wasn’t close to being fluent. Two years would ultimately fix that. But here I was, my first night in the country, trying to bond with my host family and – in my eyes – failing miserably.

Seeing my discomfort, my host grandfather took me by his very callused hand and escorted me outside the hut. He looked me in the face and asked me what was wrong. I told him, “Me siento mal.” – “I feel bad.” But for those of you Spanish speakers, you know that is not really how you say, “I feel bad” – it actually translates to “I feel sick.” I continued to tell him that I just don’t speak Spanish well enough to tell him how guilty I feel, and that it simply wasn’t fair that I had the experiences I had. He slowly lifted his hand, signaling me to stop talking. And that’s when he said:

“Somos pobres, pero no tenemos hambre.”

“We are poor, but we are not hungry.”

He explained that he had never been to school, but his kids went to some school, and that he had already attended his grandchildren’s high school graduations. He told me that…

- I can’t feel bad about where I came from; that if I wanted to be a good volunteer, I needed to stop focusing on the past and instead should focus on where I want to go in the future.

- even after I learn to speak the language, I should listen first.

- growing up in a “developed” country does not mean that I am better off than those growing up in “third world” countries.

- just because we are poor, doesn’t mean that we can’t provide for our family.

It was an incredible night for me, even if it was a normal Thursday for him. I learned about resiliency. I learned to be humble. I learned to be appreciative. I learned about Ecuadorian culture. I learned to listen. And I learned that some stories are worth telling, over and over, year and after year, because they matter. They change lives. They bring attention to the underserved. And they highlight the importance of words. For me, it was six words, from an 80-year-old man, outside of a mud-brick hut, in a tiny town in Ecuador. For you, it may be more; it may be less. But whatever it is, pay attention. Listen. Because it may just change your life.

###

Editor’s Note:

What Paul didn’t mention is that he is also an incredible musician who wrote a song inspired by the smiles he was surrounded by in Ecuador. Check this out:

Paul and another Peace Corps volunteer also led what they called “Hope Camps,” where they worked with kids on self-esteem, music, and just general fun. All their families worked on banana plantations and never had time off. But Paul and the other volunteer worked with the plantation owners to give the parents one lunch off so that they could watch their kids sing.

“I had the kids write down one sentence about anything – ‘I love meatballs,’ ‘Soccer is my favorite sport,’ ‘Edgardo can’t sing’ – and then I took those sentences and turned them into a song that we all sang. So, while the overdub is a song I wrote about the experience, the song where all the kids are laughing and smiling is a song that they wrote,” Paul shared.

What makes this song – and the smiles seen in the video – extra special is that these kids didn’t let their circumstances break their spirits. As Paul explained to me, “Most of the families lived in a community that was built on top of an old dump – those white poles are letting out the methane that builds up under the ground. Yet, the people there could not be nicer. Even when I came around with my camera, people invited me into their homes to eat a cookie, have some water (or a beer if they had it), and spend time with their families. It’s why the program is two years long. You need to build trust in order to be let in. Trust takes time.”

Now you can see why this experience changed Paul’s perspective on life, and what it really means to live a good life.

Paul Borovay

Paul is a native Californian who, after spending a few years in Ecuador as a Peace Corps Volunteer and several years in the Midwest as an attorney, appreciates the finer things in life, namely, weather (all types), music (recording and building guitars), writing screenplays (he’s optioned one so far, but he has a few others if you're interested), and intellectual property law (it’s what he does, every day).

Having started in private practice, Zebra was actually a client from his first day as an attorney until he came in house in 2019. Currently, Paul lead’s Zebra global trademark, copyright, and advertising group. He also advises Zebra’s U.S. sales teams on government procurement matters.

Zebra Developer Blog

Zebra Developer BlogZebra Developer Blog

Are you a Zebra Developer? Find more technical discussions on our Developer Portal blog.

Zebra Story Hub

Zebra Story HubZebra Story Hub

Looking for more expert insights? Visit the Zebra Story Hub for more interviews, news, and industry trend analysis.

Search the Blog

Search the BlogSearch the Blog

Use the below link to search all of our blog posts.

Most Recent

Legal Terms of Use Privacy Policy Supply Chain Transparency

ZEBRA and the stylized Zebra head are trademarks of Zebra Technologies Corp., registered in many jurisdictions worldwide. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Note: Some content or images on zebra.com may have been generated in whole or in part by AI. ©2026 Zebra Technologies Corp. and/or its affiliates.